A conventional watermark typically comprises a visible logo or pattern designed to deter counterfeiting and can be found on various items, from currency notes to postage stamps. You might have encountered a watermark in the preview of your graduation photos, for instance. However, in the realm of artificial intelligence, watermarking takes a slight twist, as is often the case in this space.

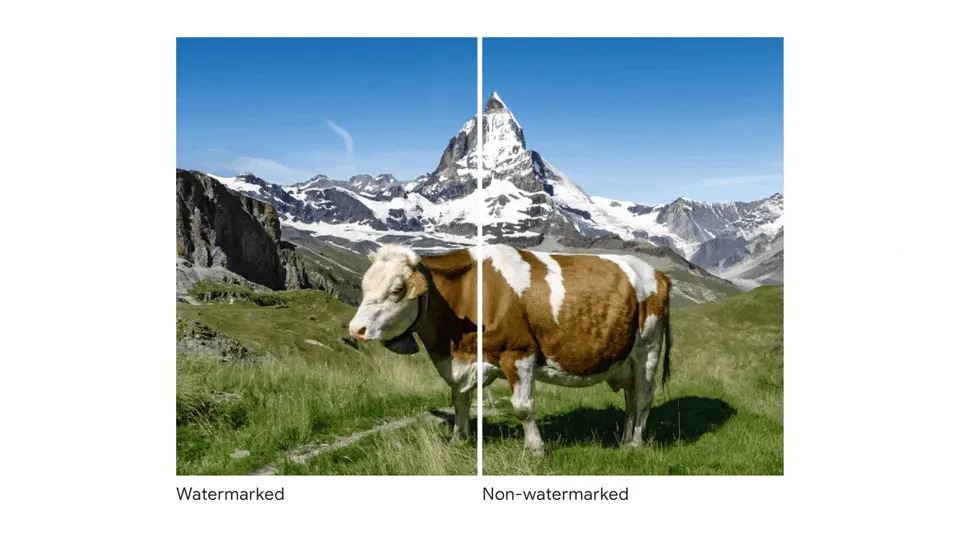

In the context of AI, watermarking serves the purpose of enabling a computer to discern whether text or an image has been generated by artificial intelligence. But why apply watermarks to images in the first place? Generative art provides an ideal environment for the proliferation of deepfakes and other forms of misinformation. Therefore, despite being invisible to the naked eye, watermarks can serve as a defense against the misuse of AI-generated content and can even be incorporated into machine-learning programs developed by tech giants like Google. Prominent players in the field, including OpenAI, Meta, and Amazon, have also committed to developing watermarking technology to combat misinformation.

To address this issue, computer science researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD) undertook a study to examine and comprehend how easily malicious actors can add or remove watermarks. Soheil Feizi, a professor at UMD, informed Wired that the team’s findings confirmed their skepticism regarding the reliability of existing watermarking applications. During their testing, the researchers found it relatively simple to bypass the current watermarking methods and even easier to affix counterfeit emblems to images that were not generated by AI. Most notably, one team at UMD developed a watermark that is exceedingly difficult to remove from content without fundamentally compromising the intellectual property. This innovation enables the detection of stolen products.

In a collaborative research endeavor involving the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Carnegie Mellon University, researchers discovered that watermarks were easily removable through simulated attacks. The study identifies two distinct methods for eliminating watermarks in these attacks: destructive and constructive approaches.

In destructive attacks, malicious actors treat watermarks as if they are an integral part of the image. They achieve this by adjusting elements like brightness, contrast, using JPEG compression, or simply rotating the image. While these methods effectively remove the watermark, they also significantly degrade the image quality, resulting in noticeable deterioration.

Conversely, constructive attacks for watermark removal involve more delicate techniques, such as the application of Gaussian blur.

While the efficacy of watermarking AI-generated content needs improvement to withstand simulated tests akin to those conducted in these research studies, it’s conceivable that digital watermarking may evolve into a competitive race against hackers. Until a new standard emerges, we must rely on promising tools like Google’s SynthID, an identification tool for generative art, which will continue to undergo refinement by developers until it becomes mainstream.

The timing for innovation from thought leaders couldn’t be more opportune. With the impending 2024 presidential election in the United States, AI-generated content could play a significant role in influencing political opinion, particularly through the use of deep fake advertisements. The Biden administration has also acknowledged this issue, expressing reasonable concerns about how artificial intelligence can be misused, particularly in spreading misinformation.